Berlin, 1990. One November day Gilbert Furian stood on an escalator climbing upwards in a supermarket on Alexanderplatz. While going up, he recognizes the man passing slowly by going downwards. It’s an old foe. The Berlin Wall is gone, two Germanys have become one, and now Furian finally found his former tormentor. On top he changes escalator and goes after the man.

The end of East Germany swapped upper and lower hand, winner and loser, in the reunified German society. It’s easy to imagine the difficult art of shaping two nations with unimaginable differences into one. Especially when one side are bringing open wounds and old accounts to the marriage. The fact that the years after 1989 remained civilized and not, as in Romania, where the Ceauceascu’s were shot down in a backyard cannot be underestimated, says author Gilbert Furian. He himself was in the clutches of an Stasi-interrogator.

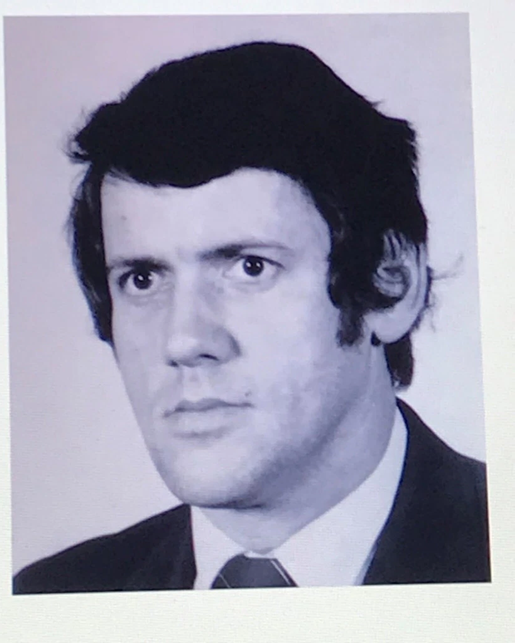

This journalist have over the course of three years, corresponded with Gilbert Furian. A German author, mediate of history and perennial dedicated guide in the former Stasi prison Berlin-Hohenschönhausen. Where he once were imprisoned himself. Furian has vividly talked about the dark sides of GDR, the art of self-control, forgiveness and a higher goal in mind than just revenge.

About:

- Born 1945 in Görlitz

- Expelled by FDJ (young communists) because of divergent political views

- Forced to quit studies at Leipzig University in 1970 due to connections with Church communities

- Arrested and sentenced to prison for 14 months in 1985 for ‘writing which likely would harm interest of East Germany’

- Attented Round-table talks in 1990 for New Forum in Berlin-Pankow area

- Starts guiding tours at Berlin-Hohenschönhausen in 1995. Have since led thousands of visitors through the memorial

- Living with his wife in Fürstenwalde outside Berlin

“The atmosphere in 1989 was shaped by the fact that people came with candles in hand from churches and shouted, ‘no violence’ “, says Furian. “My first feeling when I saw my old interrogator was not hate. I only thought of interview him for my book”.

Back in the supermarket on Alexanderplatz Furian sees the man stops at a garbage station and goes straight on.

“I say his name, and he turns and exclaims ‘Gilbert! After four years, he knew immediately who I was. My heart pounded, but not from fear. I was the winner because his whole world had just collapsed”.

Furians book would be Flour from Mielke’s mills – Political convicted. With his own Stasi-interrogator major Wolfgang Mascher as an integral source. The book is based on Furians own experiences, interviews and his hefty case in the Stasi archives, consisting of monitoring reports, descriptions of Stasi visits to his apartment, conversations with landlords and a lot of minor details, like what time he gets up in the morning and he appears unshaven. Many would think precisely such reading of surveillance makes it unfeasible to forgive? And therefore many Germans feel it’s offensive to the sense of justice, that only two Stasi employees ever received a prison sentence after the reunification.

“I wanted to learn about the man who questioned me. It was a rule of decision that my interrogation leader’s work could not bring him to justice. I respect that. Although many of my colleagues who also was detained, fells very different about it”, emphasizes Furian.

Who is Bauerschmidt?

In March 1985, Gilbert Furian worked at a planning office. In his spare time, he wrote articles on the punk environment in East Berlin. His mother had retirement permission to cross the border and was handed the articles with her on a trip to West Berlin. Her smuggling was discovered.

“ I underestimated the whole thing totally”, admits Furian. “I thought, if they caught it, they would pull me in, scream at me and send me back home”.

Early morning in March 1985 four men in plainclothes asks him to follow with them and ‘clarifying facts’. He ends up in a van with five cells and zero windows jolting through East Berlin. The car stops at Stasi prison Hohenschönhausen where interrogator major Wolfgang Mascher waits in room 385.

Thin curtains cover the only window in the interrogation room. There was a wardrobe and a filing cabinet along one wall, on the desk a telephone and a small box with alarm buttons. Interrogations lasted from morning to late night, interrupted only by lunch, which took place in the cell. For seven months the two men only meets each other in room 385.

“He asked, I answered, and then he wrote down my answers”, recalls Furian. “One day he made a mistake and showed a document in which his name was on. Knowledge I kept to myself. As a kind of joker in our questioning poker. I knew something he didn’t, and it was very satisfying”.

“He often asked me if I knew one ‘Bauerschmidt’, which surprised me. I always replied that I knew the sculptor Marie-Luise Bauer Schmidt. He wrote it down again and again, even though it wasn’t the answer he was fishing for”.

After the interrogation Furian was handed Wolfgang Maschers handwritten notes for perusal. He always noted the heavy bureaucratic language, but never saw a typo. Occasionally Mascher would tell how a bird had messed the flower box on his balcony or what his sons wanted to study.

“His interrogation strategy was obviously kindness. But with an ulterior motive”, Furian explains. “He never threatened me. Never shouted. I think it made him a far more successful interrogator than those who roared and threatened”.

Furian served seven months before he was told of release and a sent off to West Germany. An offer Furian rejected.

“Right until the very day I wasn’t sure if they would deport me or not. An officer asked me how a release sounded and I answered ‘very good, if the direction is correct’, meaning not being sent to the west”.

He was then released and allowed to remain in East Germany. When released into freedom, it is from a prison in Cottbus with a ticket back to Berlin. Back home his apartment stood as he left it, that morning he left for work.

– What did you do first?

“Johannes Brahms”, accentuate Furian with exclamation points! “I put his first symphony on and turned up. I could not bear to talk to someone. And Mozart had been too silly”.

Winds of change

After the Berlin Wall fell Stasi’s archives was opened. Gilbert Furian expected a file, but was left stunned when a Office clerk came with three huge folders on a trolley. He read to his surprise, that the monitoring of him already began in 1966. The reason is a comment to colleagues that the upcoming elections are not free. Criticism of the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 brings him more of Stasi’s attention. In the hands of Wolfgang Mascher his code name was ‘Schreiber’, but in other reports he is called both ‘Copernicus’, ‘Revisionist’ and ‘Thursday’s Circle’.

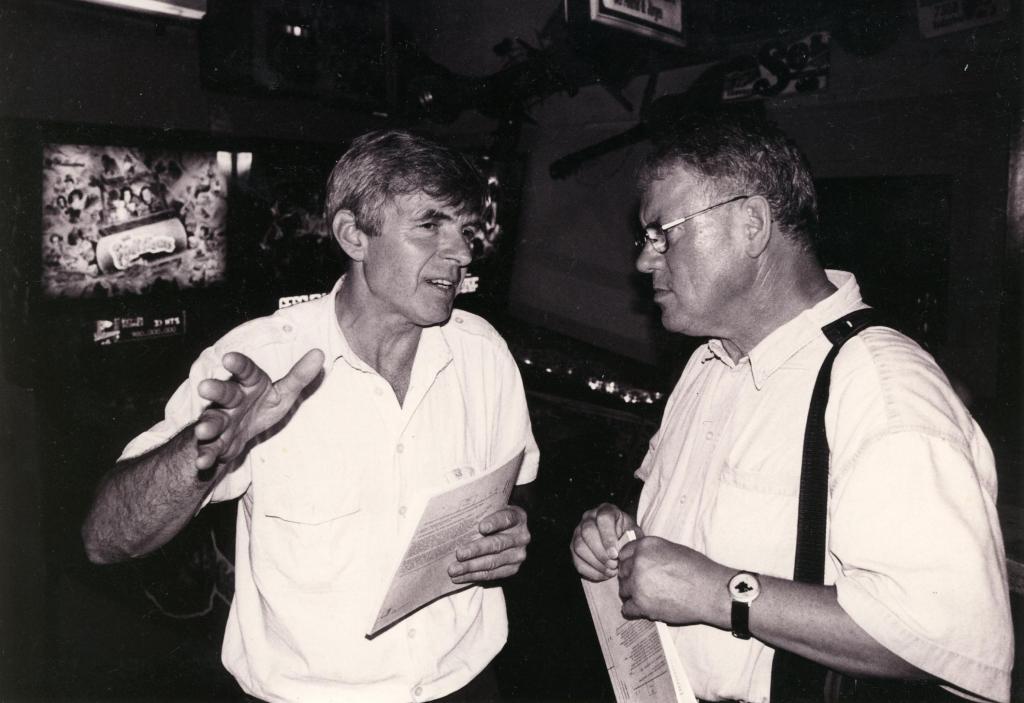

In the wake of the reunification around 92,000 Stasi officers was dismissed. A past in the Stasi is no way to professional advancement. After a short intermezzo as security chief at a hotel Wolfgang Mascher ends up with an early retirement. In early 1991, Gilbert Furian knocks on the door in a dismal communist apartment block. Ironically the flat lies opposite of the former Stasi headquarters in Berlin, which today is a museum and memorial. Inside, he was not greeted by luxury. Wolfgang Maschers apartment exudes nothing in socialist privileges.

“My wife thought it was insane to meet with him. But I wanted to know this man. Every time we met, I put my feelings aside. The contempt I felt for his work. I was never provoked by his views, because I knew his power was gone and my life was better than his. I was the winner and therefore had profit in these conversations. “

It was the first of many meetings between the two men, formerly enemies, but now got together in a mutual understanding of the need to talk. Wolfgang Mascher cut off all contacts with his past and even left the apartment block where many Stasi officers still lived because he could no longer endure the whining generals and officers, he drove with in the elevator every day.

The good and the evil

“I have always spoken openly about my experiences because something in me said, that if I didn’t it would strangle me,” says Furian.

Since 1995 he has been a tour guide in Hohenschönhausen which he knows so well from the inside. He passes on the story about an East Germany, who pretended to know better than its citizens and oppressed in that spirit.

– Who was Bauerschmidt then?

“Mascher told me after the reunification, he hoped to prove a connection between me and Jürgen Bauerschmidt, who was involved in the civil movement, since it would have worsened my situation.”

– How do you put your feelings away with someone who has made you suffer?

“By not only looking at the function, but on the person behind that function”.

– It sounds like you have forgiven him?

“To his advantage speeches, that he answered all my questions and made his knowledge available to historians. He told for instance which rooms was for questioning and which ones were not. I think he wished to compensate for something with it. The fact that he behaved like someone who wanted to do right, made it possible for me to forgive him”.

– Was Wolfgang Mascher a better person than the work he did?

“That’s a really good question. I did not know him as a father, husband or colleague, but our meetings gave me the impression of a man, where person and work were one. In the end, he worked on getting people convicted who was innocent in the legal sense. Something many would find utterly wrong”.

– Why did you not seek revenge?

“It’s important that I give a complex picture of a near past with much information, some evaluation and no unilateral judgments. In East Germany, you didn’t fear unemployment or homelessness as many do today. And what is created by that? Frustration, doubts and longings for something else. We must remember that the East German regime controlled what could be seen, read and be written. For that, no State in the world can be loved. I hope my tours serves as more than a tourist magnet, but as a place of information, which achieves insight to appreciate democracy despite all the errors”.

“A civilized agreement made reconciliation possible between Wolfgang Mascher and me. And reconciliation is always a good bargain for both parties”.